Spend some time in the trenches at a software as a service (SaaS) or e-commerce company and you'll find a prevailing opinion that traditional release management processes don't keep up with the rapid pace of application changes and rising system complexity. SaaS and e-commerce environments are the ultimate example of IT moving from being a supporting cost center to the actual source of revenue production. For SaaS and e-commerce companies, the application release process is what governs their "factory floor" and this process needs to be run with as much predictability, measurability, and automated efficiency as any modern manufacturing process. To make this governing process run smoothly you need to handoff well defined units of change from one part of the process to the next, and this is where a package-centric application release methodology comes into play. The package-centric application release methodology augments traditional change management to help implement and execute change.

Traditional vs. Package-Centric Methodologies

Traditional release management methodologies are dominated by human process definition and organizational workflows that govern how change tasks should be controlled and who should carry it out. Toolsets to support these traditional methodologies are centered around task approval, auditing, and planning. In other words, a traditional release management methodology is all about managing people and their activities. These human-oriented workflows are important, but on their own they do little to solve the inefficiencies and complexities that plague technicians in SaaS and e-commerce companies when the time comes to execute procedure to carry out those changes. Plainly put, you can get a good handle on what all your people are doing, but you don't get a good handle on how their changes are technically performed.

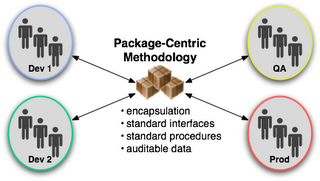

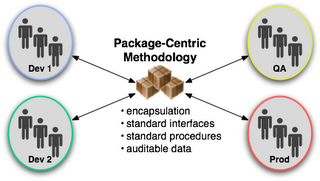

In contrast, a package-centric release management methodology focuses on how to facilitate collaboration of decentralized groups to coordinate the implementation of change. Under this methodology, the product of each team is released as a standard unit, one that contains instructions on how to apply the change as well as any relevant content needed for the change. These standardized units of change enable an automated change management approach that rationalizes and coordinates changes originating from disparate teams but each potentially effecting the greater application service operation. In other words, package-centric release management methodology focuses on format, modularity, mechanisms, and technical workflow all in the context of the larger integrated application.

The basic element of the package-centric methodology is, not surprisingly, the package. The package concept prescribes a standard unit of distribution as well as standardized methods for installation and removal. The essential benefit of formal packaging is the provision for changes to be predictably migrated, done, and undone. A package also carries with it essential information like what version it is, who made it, and what does it depend on. Ultimately, packages become the common currency of change within the IT organization.

What belongs in a package?

One often imagines a release to be a distribution of an entire application. In reality, for online systems, change happens at a much more granular level. One typically observes several kinds of changes released to live environments:

- Code: Application files executed by the runtime system. This could be compiled objects or interpreted script.

- Platform: Files that comprise the runtime layer. This is generally server software like Apache, JBoss, Oracle, etc.

- Content: Non-executed files containing information. These could be media files or static text.

- Configuration: Files defining the structure and settings of an online service. These could be files for configuring the runtime system or the application.

- Data: Files containing data or procedures for defining data. These could be database schema dumps, SQL scripts, .csv files, etc.

- Control: Configuration and procedures consumed by management frameworks

Within the package-centric paradigm, each type of change noted above is bundled, distributed and executed via a package.

Standard vehicle of change

The package serves as a vehicle of change, both as a unit of transmission between teams, but also as a standard means to affect the change within the context of the running application service. The package concept helps cope with rising complexity by encapsulating change-specific procedures and underlying tools behind the package's standard interfaces. In an object-oriented fashion, the package provides the standard interfaces and encapsulation needed to run efficient operations. Teams no longer have to understand the internal structure and procedures in order to apply another team's change.

Scaling up

Because packages establish a standard interface to distribute and execute change, an IT organization can more readily scale up operations. Knowledge transfer no longer needs to be done between individuals but can instead be explicitly specified within the package. By declaring the essential knowledge and process within the package, teams can more quickly execute change by avoiding repeated inter-personal communication. Because changes are packaged, they can be stored in a repository to facilitate auditing and reporting. Package-centric change also makes it possible to leverage a generalized automation layer to rationally execute changes en masse. Automation is key to gaining the efficiency needed to run any SaaS or e-ecommerce application.

The human workflow emphasized by traditional release management methodology is an important component to governing the business service's "factory floor" . The package-centric methodology picks up where the activity planning and coordination leave off by assisting the technicians to distribute and apply change.

In future posts I'll discuss the various aspects, benefits, and examples of the Package Centric Release Methodology.

Alex Honor |

Alex Honor |  Friday, February 1, 2008 at 10:35AM

Friday, February 1, 2008 at 10:35AM  Patterns

Patterns